In the years following the pandemic, art ecosystems in China have undergone profound change amid a slow economic recovery. With the property-driven funding model in decline, art institutions in southern China are adapting and seeking sustainable strategies to build capacity while navigating this transitional landscape. Across Hong Kong, Macao, and the broader Guangdong region, many institutions have embraced more open and innovative operational models that promote cross-border engagement and dialogue, injecting renewed vitality into the regional art scene. Together, these growing symbiotic networks foster cross-regional collaboration and chart open new directions for art in the Greater Bay Area.

Hong Kong: Driving Connectivity

The art scene of Hong Kong remains resilient despite economic uncertainties. M+, a museum dedicated to contemporary visual culture, exemplifies this strength through diversified funding streams that sustain its blockbuster exhibitions and programmes. As a pivotal player in Asia and the global art scene, the museum advocates for cultural exchange and dialogue. Its exhibitions often present historical reviews on overlooked narratives, building gateways to connect regional and international discourses. Dr. Mo Wu, Sigg Curator at M+, explained that the museum adopts a multidisciplinary framework to curate within visual culture. This approach traces fluid historical threads across diverse creative practices, weaving together lesser-told stories and curating a more dynamic narrative within a broader cultural context.

Recent exhibitions such as ‘Canton Modern’ (2025) revisited and reconstructed the cultural identities of 20th century Cantonese art and visual culture, spanning the 1900s to the 1970s—a narrative long considered marginalised within modern art history. Looking to the contemporary, the Sigg Prize, a biennial art award, spotlights emerging artists across Greater China. The 2025 edition recognises the breadth of art practices from southern China, honouring Wong Ping from Hong Kong and Heidi Lau from Macao as the joint winners for their distinctive approaches to moving image and ceramics, respectively.

“Exhibitions, however, are not the only avenue for M+ to build networks and foster cross-regional interactions,” emphasised Dr. Wu. The museum actively pursues initiatives beyond exhibition-making, encompassing talks, publications, and curated tours. One such tour brought museum patrons and curatorial professionals to visit institutions and artist studios in nearby regions, including the influential art collective Yangjiang Group in Guangdong. This encounter gains further resonance through the museum’s latest Sigg Collection exhibition, ‘Inner Worlds’ (2025), which features works by the Yangjiang Group from the 1990s to the 2010s. Their pieces challenge the conventional aesthetics of calligraphy through free-spirited transformations and the use of everyday materials—crumpled xuan paper arranged atop massage machines to resemble flowing rivers, wax moulded into scholarly rocks, and calligraphy written on PVC plastic sheets. These works invite viewers to reconsider the connections between tradition and the everyday. Looking ahead, the museum plans to introduce more interactive public programmes with the collective to further activate exhibition engagement.

Shenzhen: Expanding Horizons

Just an hour’s bus ride from Hong Kong, the Sea World Culture and Arts Center in Shekou, Shenzhen has established itself as a hub for art and design since its founding in 2017, in partnership with the Victoria & Albert Museum. As a cultural and commercial complex, the center integrates exhibition spaces, theatres, and artist residencies alongside commercial galleries and leisure venues, forming a dynamic and collaborative environment through a distinct cluster model. Within this strategic framework, contemporary art is embedded into the broader cultural fabric through thematic exhibitions held year-round. Zhang Xijia, Director of the Sea World Culture and Arts Center, explained that the center’s diverse stakeholders are pivotal in cultivating a creative cluster, one that helps organically incentivise collaboration, knowledge exchange, and symbiotic partnerships for mutual development.

Contemporary Chinese art history remains central to the center’s exhibition strategy, as underscored by major solo shows of artists such as Liang Shaoji, Li Shan, and Zhou Tielun. A recent highlight is ‘Body Beyond the Rules’ (2025), a landmark exhibition by the Yangjiang Group. Echoing the collective’s concurrent historical display at M+, this exhibition extended its timeframe to encompass works created after 2020, including their latest works. This expanded presentation immersed visitors in tens of thousands of crumpled xuan paper, transforming the gallery into a vast sea of calligraphy art. Together, the exhibitions across the two institutions offer a unique opportunity to study the artistic growth of the collective, providing a specific entry point into the contemporary art history of southern China.

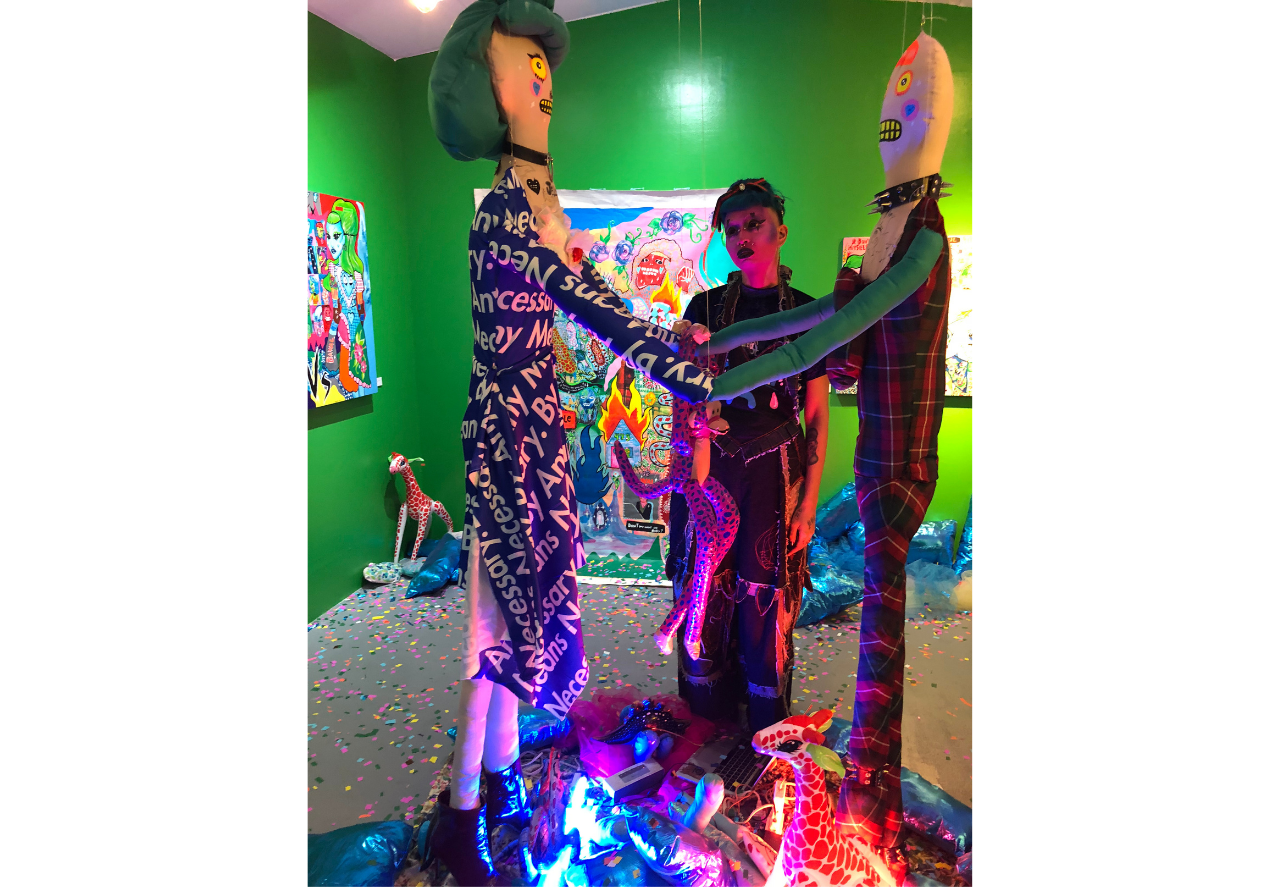

When asked about the relationship between Hong Kong and Shenzhen’s art circles, Zhang observed that the two ecosystems have evolved from a Hong Kong-centric model to a dual-core framework of mutual exchange: “Shenzhen serves as a fertile ground for growth, offering ample and flexible spaces for artists and their projects to expand beyond the spatial constraints in Hong Kong.” The center actively seeks collaboration beyond the local region, hosting an annual exhibition that spotlights cross-regional talent. This year, it presented Hong Kong artist Jaffa Lam’s institutional debut in Mainland China—also the center’s first female survey exhibition—marking a significant moment for audiences to experience her large-scale installation practices. Additionally, a partnership with the Hong Kong Arts Development Council has enabled exhibitions from Hong Kong to tour in Shenzhen, deepening dialogues and fostering sustained collaboration between the two art communities.

Guangzhou: Beyond Southern China

An hour-long high-speed train ride from Kowloon will bring you to Guangzhou, where the art ecosystem is showing signs of growth. The annual MOORDN Art Fair has expanded significantly since 2022, with increasing gallery participation underscoring the vitality of the commercial art community. Amid this momentum, Times Museum stands out with a steadfast commitment to supporting regional art practices overlooked by the market. Guided by an artist-centric principle, the museum has long prioritised its resources to nurture emerging voices and creative practices marginalised by commercial art systems.

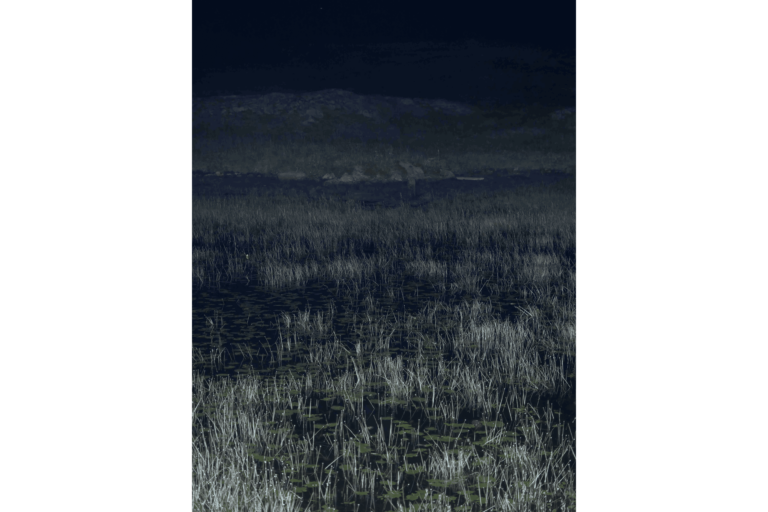

Times Museum, perched atop residential blocks in the Baiyun District, has woven its curatorial vision into the city’s social fabric through exhibition programmes that explore technology, ecology, and urban cultures. Among its flagship projects is ‘Waves Across the South’, a unique initiative offering residencies for artists to develop works or exhibitions that engage with historical and social research on southern China and the Global South. The latest edition, ‘Floating World’ (2025), featured Hong Kong artists Tang Kwong San and Yuen Nga Chi, as well as curator Chris Wan. The exhibition traced the intertwined histories of migration, identity, and cultural continuity spanning Dongguan, Guangzhou, and Hong Kong. Drawing on the nomadic traditions of the Tanka fisherfolk, the artworks reveal how geography, politics, and history have shaped the fluid identities of the Pearl River Delta. This research initiative also invited Chinese diaspora artists and practitioners from Southeast Asia, underscoring the museum’s commitment to cross-regional research and global exchange.

Nikita Cai, Deputy Director and Chief Curator of Times Museum, explains: “I initiated the project to connect southern China with diverse epistemologies, with a focus on the Pearl River Delta—a region shaped by historical waves of migration and home to the museum. The socio-cultural networks in southern China are also linked with the Global South, reaching beyond places in Southeast Asia.” ‘Waves Across the South’ demonstrates this dynamism within an institutional project, responding to the evolving conditions of southern China in relation to the world beyond. Although funding challenges persist, Times Museum continues to prioritise its programming for encounters among artists, researchers, and audiences, charting a path towards a deeper understanding and discovery of regional narratives.

Macao: Bridging Worlds

A ferry ride across the Pearl River estuary will bring you to Macao, where the art scene is striving to establish platforms for global dialogues. As a historical trading port, Macao has long been a crossroad of cultural exchange—and today, positions itself as an international stage for art and creativity. The third edition of the Macao International Art Bienniale, organised by the special administrative region, exemplifies this intercultural ambition. Titled ‘Hey, What Brings You Here?’, with Feng Boyi as chief curator, and Liu Gang and Wu Wei as co-curators, the bienniale turned Macao into a city-wide art experience. While the main exhibition was housed at the Macao Museum of Art, satellite venues extended its reach into local neighbourhoods.

The theme of the bienniale takes the form of a question—a curious, colloquial prompt that invites reflection between oneself and others; it also resonates with the fluid identities and diverse cultural context of Macao. Through this open-minded lens of enquiry, the bienniale explores the encounters between Macao and the wider world, unravelling how local and global phenomena intersect with everyday life. This vision was curated by expanding exhibition spaces into unconventional public areas in the museum. Restrooms, passageways, and rear windows were repurposed into alternative sites for display and interaction.

Among the 46 participating artists were internationally renowned figures such as Ann Hamilton, Gregor Schneider, and Xu Bing. About one-fifth of the artists hailed from Guangdong, Macao, and Hong Kong, including Jaffa Lam, Xue Song, Mark Chung, Pak Sheung Chuen, and Bianca Lei, whose works transformed the museum galleries into reflections of everyday and urban experiences. Wu observed that artists from these neighbouring regions share an affinity with the cultural and social dynamics in Macao. They possess a nuanced understanding of urban density, climates, and cultural hybridity. She further noted, “Their adaptability to repurpose alternative spaces into sites of creative engagement reflects their resourcefulness and transferable living experiences from Guangdong, Hong Kong, and Macao.”

The bienniale offers an opportunity to juxtapose artworks of varied social backgrounds, enabling cross-generational and intercultural exchange. This interplay can spark conversations and bridge regional issues with global narratives. Satellite programmes across the city further expand this dialogue through site-specific works and public art that engage communities and respond to the urban textures of Macao. The bienniale positions Macao not merely as a geopolitical meeting point, but as a window for ideas to circulate freely across borders and disciplines.

Across southern China, art institutions are contributing their unique visions to the region’s rapidly evolving art ecosystems. Despite challenges posed by recent economic downturns, these organisations continue to adapt and experiment. Collectively, they are shaping an organic network of discourse—one that encourages knowledge-sharing and a cross-regional art community. While the long-term outcomes of these interactions remain uncertain, such efforts have already charted pathways for conversations and deeper mutual understanding. Beyond the institutional perspectives outlined in this article, galleries and collectors are also playing an influential role, actively supporting artistic collaboration across southern China. Further research will be essential to assess the impact and lasting significance of these developments as they continue to unfold across the region.

In Hong Kong, which frequently tops global lists of the most expensive cities, space is the ultimate luxury. While the works of Hong Kong-based artists are often on view, the spaces where they come to life remain largely unseen, leaving us to imagine what their studios might reveal. Even for seasoned collectors, a studio visit might be a rare treat.

Founded in 1996 by seven Hong Kong-based artists, Para Site, on the eastern end of Hong Kong Island in Quarry Bay, is one of the city’s oldest independent art institutions. Their on-site residency programme supports the development of artists’ research and practice while also providing studio space on the building’s tenth floor, separate from their primary exhibition space on the top floor.

This summer, Para Site welcomed Hong Kong-based Sam Lui as their resident artist. Through her ongoing project, Wendy’s Wok World – part culinary exploration, part artistic alter ego – Lui investigates the discipline and philosophy inherent in wok cooking, pursuing ideals of purity and perfection. This endeavour has taken her from the kitchen of her family’s soy sauce factory in Sheung Shui to international venues, such as the Swiss Institute in New York in 2023, where she has prepared Cantonese classics for participants as both communal ritual and artistic statement.

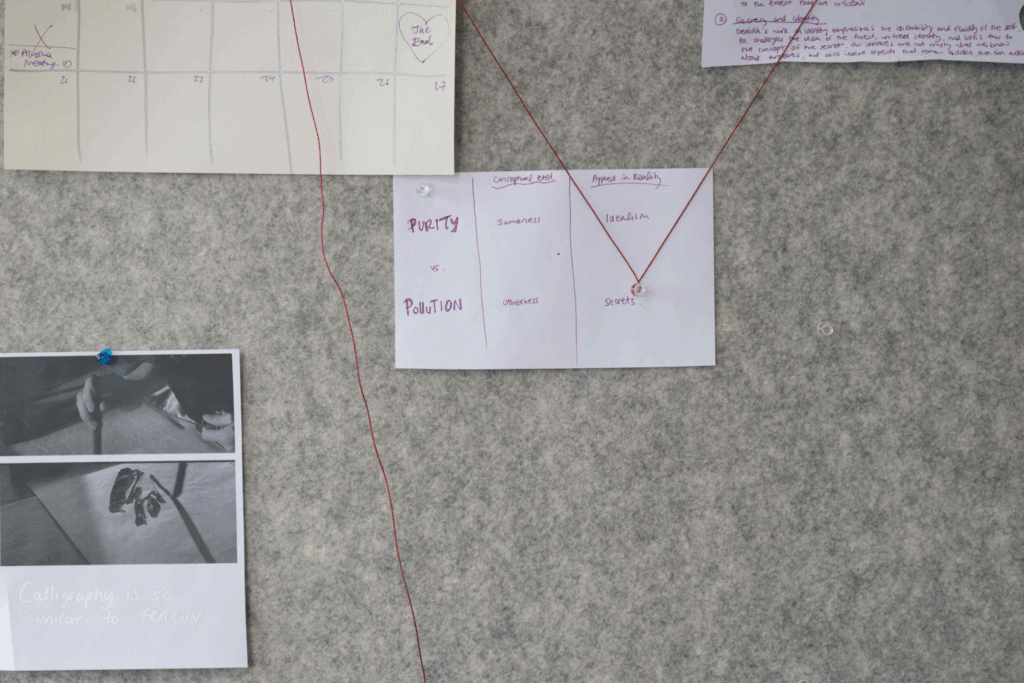

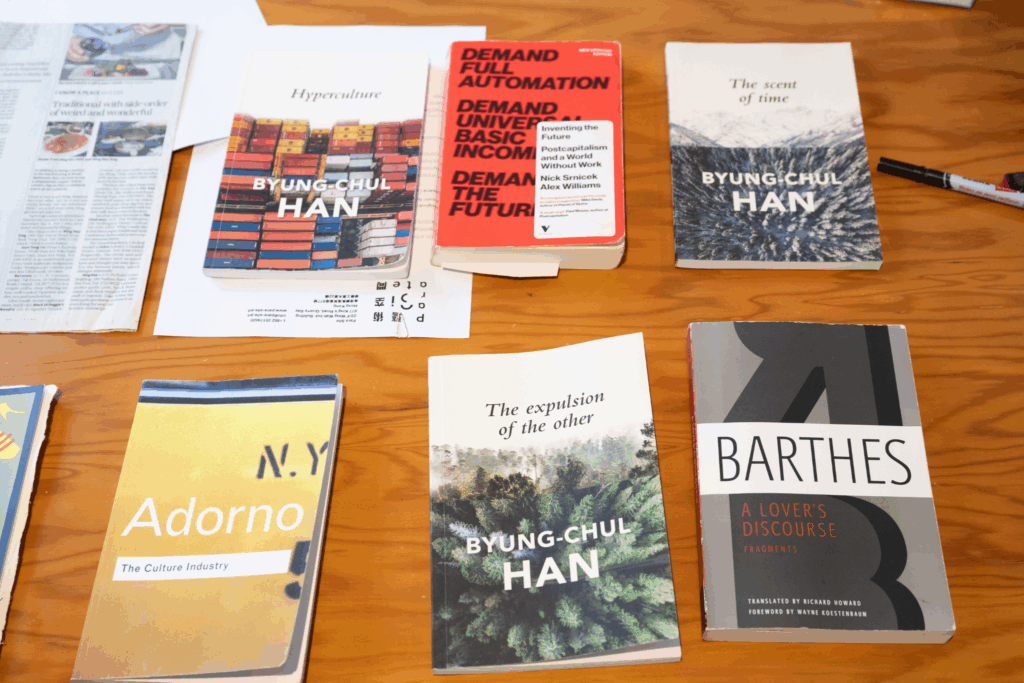

Lui’s temporary studio at Para Site resembled her interdisciplinary approach. A round table with a Lazy Susan, like those found in Chinese restaurants, anchored the space, with information on her former projects nearby. In the back, a seating area displayed books by Roland Barthes, Theodor W. Adorno, and Byung-chul Han, a nod to her background in philosophy. As part of the residency, Lui conducted a book club that invited participants to inscribe the central table with reflections on themes such as purity and secrecy, which will eventually inform an artist book examining intangible culture.

According to Junni Chen, Para Site’s Deputy Director, artist selection hinges on programmatic alignment and broader impact: “It really is what we feel connects to our programme. There are different dimensions, for example, we prefer programmes that have an element of community building and thought leadership. If they haven’t exhibited in Hong Kong before or had a milestone here, we generally want to support them.”

On the Kowloon side, in the heart of Shek Kip Mei, the Jockey Club Creative Arts Centre (JCCAC) is a former factory building that has been transformed into an arts centre, first opening in 2008. The nine-storey complex houses a mix of cafés, workshops, and studios. On its third floor sits Floating Projects, an artist collective founded in 2010 by artist, curator and former City University professor Linda Lai Chiu-han, who retired from the School of Creative Media in 2023.

Floating Projects operates as a fully artist-run, multipurpose space, part exhibition venue, part library, and part café. The exhibition area often features a range of works from the collective, spanning video, installation and sculpture. Recently on view and especially eye-catching, Monster Boxes, a work by Kel Lok and Andio Lai, comprises a wooden box which stands no more than half a metre, featuring a small circular rotating platform in the middle, onto which two small figurines, both chimaeras composed of different animal figurines, are attached by magnets. Inside the box, more figurines await configuration.

The artists describe their approach as “toy as medium”, an idea central to the collective’s spirit of experimentation. Reflecting on this ethos, founder Linda Lai explains: “There’s a lot for us to think about in terms of not doing the usual thing. What and who are being left out of the discussions because of standards or consensus? Hong Kong, like many other places, is full of standard practices.”

The studio functions as both a working space and an incubator for ideas among its members. In its mission statement, Floating Projects emphasises a collective commitment to “rigorous mutual critique” and to “an evolving approach to art-making that treats each work as an open process with generative potential.”

“We think of every member as an individual unit,” Lai adds. “Everyone has their own dynamic. We invite them to mark their calendars for when they want to do something, for what, and for how long. We want to see if there’s anything we can help with, and we also need to arrange an official in-house critique session.”

Back on Hong Kong Island in Central, and a bit away from the commercial high-rises it is typically known for, stands PMQ (formerly the Police Married Quarters), a historic site repurposed into a creative hub for independent craftspeople and artists. Tucked away on its seventh floor is the studio of Cynthia Mak.

With its inviting glass façade, Mak’s studio offers passers-by a glimpse into her colourful world. Inside, vibrant paintings and sculptures abound. A graduate of Central Saint Martins, Mak began her career in fashion before transitioning to multimedia art. Her practice has since become instantly recognisable in Hong Kong, with works being featured by the Hong Kong Museum of Art, Hermès, and Lane Crawford. Characterised by geometric abstraction and vivid hues, poppy red, cyan, and powder pink, her art draws inspiration from Hong Kong’s cultural identity. She is currently working on a large-scale abstract interpretation of a shanshui (mountain and water) painting.

“I believe that the first thing that resonates with viewers in my work is a sense of joy,” Mak notes. “Much of my abstract work is inspired by my cultural background and everyday experiences.”

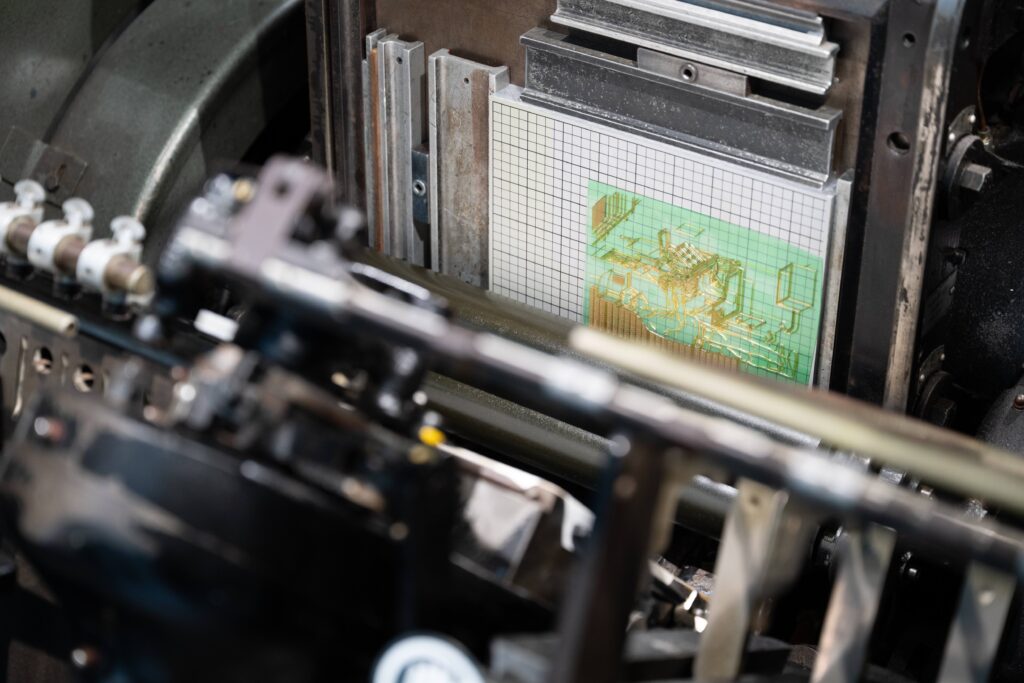

Also located in PMQ is Print Art Contemporary, operated by Hong Kong Open Printshop. Dedicated to the history and evolution of printing, the space features educational displays about Hong Kong’s print and typography heritage, including antique printing equipment and a wall-length shelf with movable type pieces.

The Hong Kong Open Printshop also operates a 4,000-square-foot professional Print Lab at JCCAC, where recipients of the annual Hong Kong Open Printshop Award (HKOP Award) complete six-month residencies that provide mentorship, materials, technical support, and an exhibition venue at the end of their residency, aligning with the Printshop’s mission of fostering and nurturing emerging talents. In 2025, the award was granted to artists Julie May and Enna Cheung Yeuk-fei, culminating in two solo exhibitions hosted at Print Art Contemporary, accompanied by live demonstrations at the Print Lab.

Together, private studios like Mak’s, institution-led residencies such as those at Para Site, artist-run initiatives like Floating Projects, and hybrid models like Print Art Contemporary and Print Lab reveal the diversity of spaces that sustain Hong Kong’s artistic ecosystem. In a city where space is scarce, these sites serve as vital environments for creation, experimentation, and community connection. Stepping inside them is to experience one of the many ways that artists often turn limited resources into expansive creative potentiality.

Most of us have heard the same tired stereotypes about art galleries: they’re “intimidating,” “posh,” run by “snobbish” gallerists, and filled with art that’s invariably “expensive” or “impossible to understand”. A recent survey conducted in the UK further reinforces these misconceptions, which include the belief that galleries only display paintings and that visitors are expected to be quiet.1

Nothing could be further from the truth at Vinyl on Vinyl Gallery in Manila and AStar Gallery in Taipei – two trailblazing art spaces that boldly dismantle such urban myths. Rejecting the white cube model in favour of a less traditional approach, both galleries offer diverse programmes that focus not only on artists who are talented, authentic, and unique, but also on connecting with audiences, building communities and forging friendships.

“I’m all about the community”, declares Gaby Dela Merced, founder of Vinyl on Vinyl, whose warehouse-cum-gallery showcases emerging trends in art and is a welcoming space for everyone. Reflecting on her deep appreciation for underground art and culture, Dela Merced does not shy away from transforming the gallery to match the energy: painting her walls an Instagram-worthy jade green (for queer performance artist Jellyfish Kisses) or a checkerboard black and white (for pop artist-illustrator Roger Mond). Street artist Dennis Bato’s site-specific installations have transformed every inch of the space into immersive, experiential environments. Formality? Not here. And yes, music plays.

Perhaps Dela Merced’s success stems from following her heart – “Authenticity is key!” she insists. An accidental gallerist by circumstance, she first studied interior design and advertising, but later followed her teenage passion for race-car driving, eventually becoming one of the few Filipinas to dominate the Asian Formula Three circuit. While racing in the US, she frequented alternative galleries such as La Luz de Jesus and GR2 in Los Angeles and made trips to Comic-Con in San Diego. As her passion for and knowledge of street art grew, so did the realisation of a calling beyond the racetrack.

From these origins, Vinyl on Vinyl was born in Manila in 2009, initially as a music-filled space to showcase her growing collection of vinyl collectables. It was in discovering a community of artists who shared her passion for making a positive impact that Dela Merced found a way to bridge the worlds of urban and contemporary art, toy art and sculpture, music and sound art – all of which inform the gallery’s programme today.

AStar Gallery’s founder, Shelley Wang, has always believed that running a gallery is about more than just selling art. “It’s about education – educating oneself and educating your clients. There is nothing more rewarding than when clients become friends,” she says. AStar’s thirty-year history is testament to her vision. The gallery’s culturally rich programme of talks, music appreciation events, and film screenings, including sharing sessions, recently featured “Faces Places,” a French documentary directed by Agnès Varda and artist JR, and hosted a live DJ performance for the opening of street artist Mr. OGAY’s exhibition.

Wang’s art journey has been less about discovery and more about reconnecting with a deep-rooted love for art. Though she didn’t qualify for art school, she majored in Japanese language and culture at university. When her family moved to Scotland, frequent museum and gallery visits in Europe reignited her passion. Returning to Taiwan, Wang’s global outlook led her to a director of sales role at a members’ club, where she met her future business partner, a Murano glass dealer. She eventually became the owner, travelling regularly to Venice for fifteen years to connect with artists and clients, and discovering a knack for building relationships.

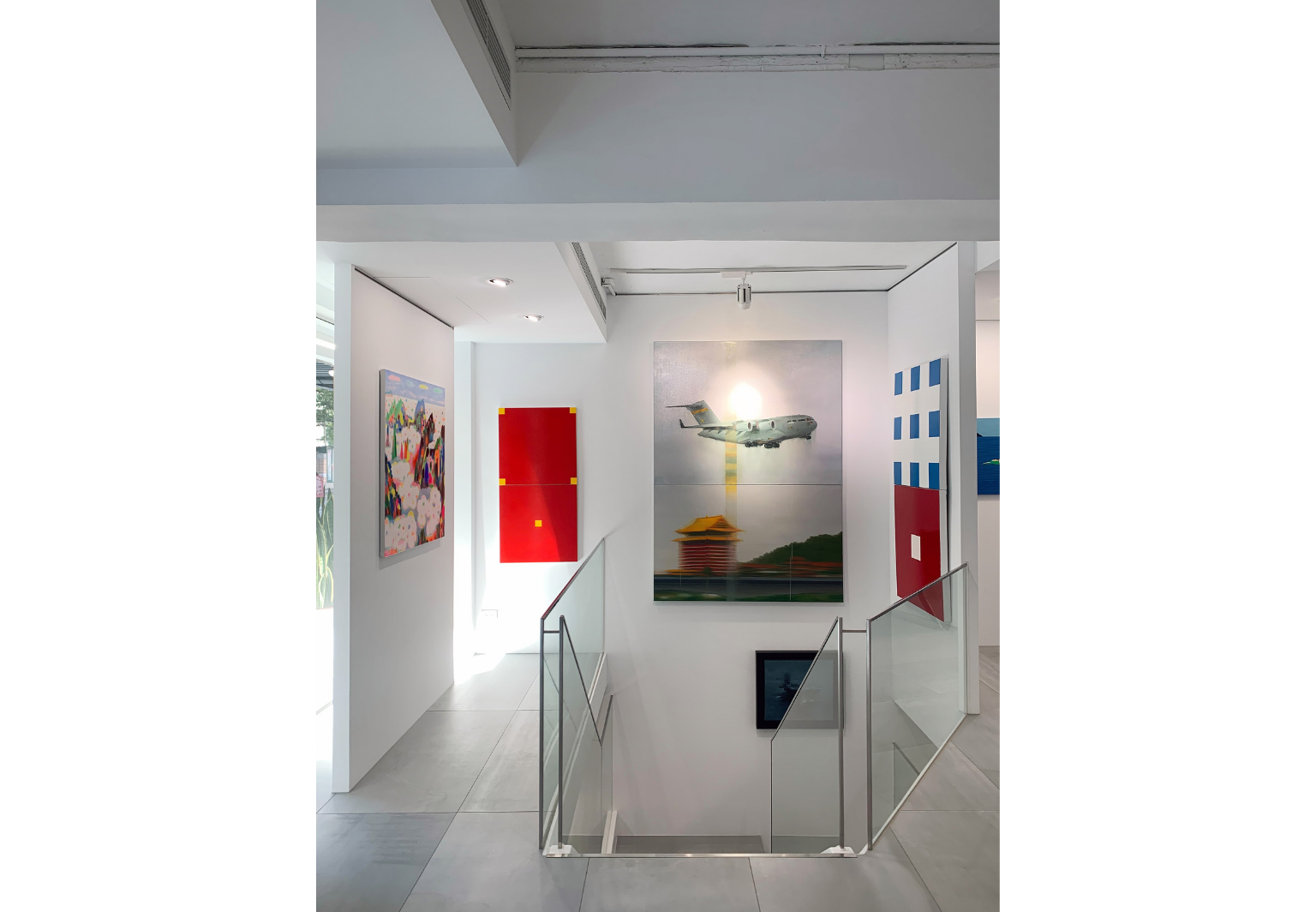

Wang’s entry into the contemporary art world was part serendipity, part practicality: she had to source art for her new multi-level space in downtown Taipei. Meeting renowned artist and professor Dean-E Mei proved pivotal, as it introduced her to Taipei’s creative and intellectual community, many of whom eventually joined her gallery.

Both Dela Merced and Wang recognise that there is no room for complacency on the road to success. While it is one thing to do well locally, both recognise the need to promote their artists internationally, primarily through participating in overseas art fairs. Many gallerists, including Stephanie Braun of Karin Weber Gallery and Rachel Lee of Soluna Fine Art, both Hong Kong-based galleries, echo this point. “Fairs are really key for meeting new (international) clients, and to showcase the best works of our artists,” Braun affirmed. Lee added that “it really is about balancing creative and business responsibilities.”

This March, Dela Merced reconnected with Hong Kong clients after having been absent since the pandemic. Aligning with her vision to highlight peripheral art forms from the Philippines, she returned with a solo presentation of surrealist paintings, unconventional objects, and quirky ‘Ohlala’ figurines by gallery artist Reen Barrera at Art Central. “Fairs are the best way to showcase Filipino artists on the world stage,” she says, calling Hong Kong “the original melting pot”.

Wang, meanwhile, debuted at Art Central with two artists from Taiwan: Dean-E Mei’s multimedia Dadaist works featured prominently in the Fair’s “Legend” section, while modern colourful landscape paintings by young contemporary artist Chong-Xiao Zheng were presented in a solo booth.

Both Dela Merced and Wang were delighted at the exposure their galleries and artists received in Hong Kong, and especially at the new friendships they made with visitors from around the world. With Dela Merced’s infectious energy and Wang’s easy-going charm, it’s no wonder that many of these new friends have since visited their galleries in Manila and Taipei. Snobbish? Certainly not.

Ever the athlete, it comes as little surprise to learn that Dela Merced remains true to her love of sport by playing for the Philippines Women’s National Flag Football team; Wang continues to import Venetian glass, and curates the international pavilion for the Glass Art Festival in Hsinchu – sixteen years and counting! Their journeys might be worlds apart, but at the heart of it all, Dela Merced and Wang share the same secret to success: authenticity – a genuine spark that fuels their passion, binds their communities, and keeps their creative fires burning bright.

1. https://museumobserver.com/a-fifth-of-uk-adults-fear-theyll-find-an-art-gallery-too-posh/

In Hong Kong’s vibrant art scene, collectors Monica Hsiao and Henry Chu offer compelling perspectives on the motivations and philosophies that drive their acquisitions. More than mere accumulation, their collecting journeys represent profound explorations of personal identity, emotional resonance, and the narratives embedded within art itself.

Monica Hsiao: Weaving a Tapestry of Life Through Art

For Monica Hsiao, founder and CIO of Triada Capital, the story of collecting blossomed from humble origins, which at first grew from her and her husband’s interest in antique curios, porcelain, and prints. “Our initial collection consisted mainly of Chinese ink paintings and Japanese woodblock prints,” she recalls. The couple’s collecting trajectory has been intricately woven with personal growth; in the early stages, they focused their education on the works of Renaissance painters and the Old Masters. However, as time passed, their interests expanded to embrace the vivid realms of modern and abstract art.

Hsiao also emphasises the importance of familial influence in shaping her passion for the arts. “The arts and humanities have been deeply cherished on both sides of our family,” she shares, highlighting a lineage that includes musicians, painters, writers, and photographers. This legacy inspired her to instill a love for art in her own children. Prioritising access to cultural institutions, Hsiao and her husband strategically chose homes in New York and London within walking distance of major museums. This immersive environment nurtured her daughters’ artistic inclinations, with both continuing to sketch and paint as they pursue their respective careers in medicine and technology.

In her dual role as a hedge fund manager and art collector, Hsiao passionately expresses that the intrinsic value of art transcends the rigid confines of market analytics. “For us, the collection of art is not only for investment or a storehouse of asset value, but first and foremost, for the enrichment of life,” she states, highlighting a belief in the emotional resonance and intellectual stimulation that art provides—elements that cannot be quantified in mere numbers. Nonetheless, she recognises the practical necessity of understanding market trends, especially when contemplating significant acquisitions, and she is fascinated by the interplay of the social, aesthetic and economic factors that shape how art is valued and traded.

Throughout her collecting journey, Hsiao underscores the importance of engaging with the narratives that breathe life into each artwork. She describes a small piece by Swedish artist Andreas Eriksson by her bedside: “It is an abstract that evokes the sound of clear mountain water traversing over pebbles, and it is the most calming image to start the day with.” Having travelled to Seoul to meet Eriksson at his first solo exhibition in Asia, and having collected since then a number of his works, her commitment to understanding the backstory of each artist cultivates a deeper appreciation for the artist’s vision behind his or her body of works, which is a critical pillar of her collecting philosophy.

Hsiao particularly values artworks that provoke introspection and offer insights into the human condition. “I admire artists who have something to say,” she asserts. Travelling offers collectors opportunities to support local artists. On a trip to Vietnam, Monica and her husband spent hours at the atelier of Vu Duc Trung, learning about the painstaking process of layering to create a series of ethereal lacquered discs, works that were previously exhibited at the Hanoi Museum. “Meeting artists adds a new dimension to the engagement we have as a viewer. Understanding their emotional inspiration and technique enhances our attachment to the work.”

Sometimes, buying art may be a nostalgic response, such as when Hsiao saw the Hong Kong collection by Matthew Brandt. “Hearing about Matthew’s philosophy behind the merging of his photography and glasswork, and how he embedded sediment from our city to press into the image of old Hong Kong commercial buildings, definitely was a big factor in moving us to buy his work ”, she notes. Hsiao’s collection also features one of the earliest pieces she bought from a Hong Kong gallery, Takesada Matsutani’s “Slow-Slow” (2020). Her appreciation for Matsutani’s multi-dimensional work was deepened by an encounter with his exhibition in Europe and studies of Gutai contemporaries like Kazuo Shiraga and Sadamasa Motonaga. The artwork’s “elegant simplicity” captivated her, reflecting an emotional connection that often takes precedence over market trends.

Hsiao’s curatorial approach focuses on creating a harmonious dialogue between artworks and their environment. She meticulously considers architectural elements like lighting, color palettes, and spatial dynamics. “For example, we made a conscious decision to position a bold, red piece by Alexandria Smith across from a blue, soft, cool-toned work by Salvo,” she explains. “Smith’s sculptural piece adds depth, while Salvo’s nocturnal moonlight softens the space. The two works, while created in very different contexts by artists of different eras and backgrounds, were connected by their similarly surrealist theme.”

Hsiao encourages aspiring collectors to embrace the journey of discovery and cultivate relationships within the art community. “Stepping into the world of art collecting is like opening a door to endless possibilities—each piece represents a story waiting to be discovered,” she advises. Ultimately, she advocates for building a collection that reflects personal values and experiences. “Let your heart guide you to what resonates,” she urges, emphasizing that a collection’s true essence lies in its connection to the collector’s identity and unique journey.

Henry Chu: Finding Resonances in a Digital Age

Henry Chu, a Hong Kong-based digital artist, offers a complementary perspective on collecting, shaped by his own creative practice and his engagement with contemporary art. Chu’s entry into the art world was serendipitous. A web designer turned artist, his transition began in 2000. “My first artwork, TV Clock, was created in 2005,” he recalls. However, it wasn’t until 2015 that he began collecting, a pivotal moment that redefined his relationship with art. “When you buy art, you are also purchasing a fraction of the artist’s life,” he observes.

Chu emphasizes the importance of research and engagement for those new to collecting. “It’s essential to do your research: talk to the artist, engage with the curator, connect with the gallery, and converse with collectors. Stay open-minded, be informed, and always follow your heart.” Such practices, he believes, enable collectors to identify art that resonates on a personal level, fostering an authentic connection with each piece.

Reflecting on his experiences as both an artist and a collector, Chu draws a distinction between art buyers and true collectors. Initially, he was drawn to prints by established artists, motivated primarily by aesthetics. However, as his collection grew, he realized that true fulfillment came from acquiring unique works that reflected his own identity and memories. “Art buyers make decisions based on value, whereas collectors seek resonance within the art they acquire,” he explains.

Chu vividly recalls his first purchase: a watercolor painting by Wong Chun Hei depicting a Hong Kong reservoir. “His work serves as a reminder that Hong Kong is indeed a beautiful city with stunning landscapes. I encountered the piece at a small exhibition hosted by a bookshop in PMQ,” he fondly remembers. This experience underscored the importance of seeking art that evokes feelings and memories.

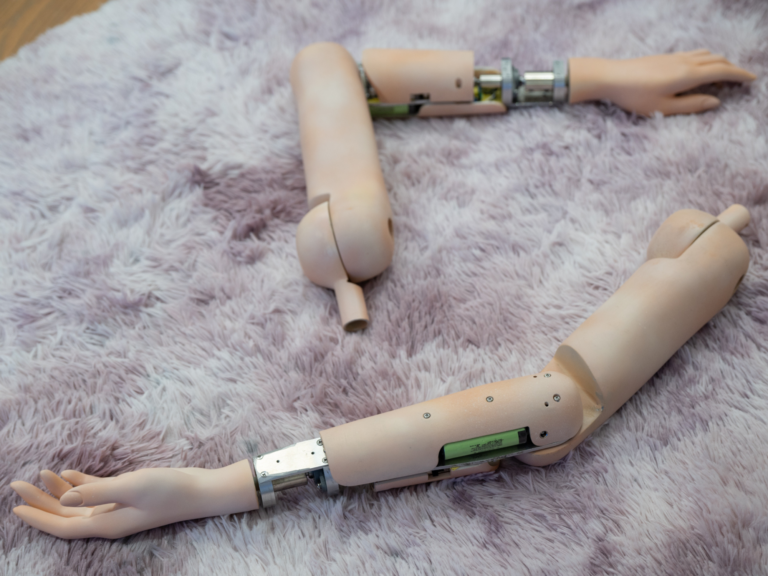

While Chu’s artistic practice centers on digital art, his collection encompasses a range of mediums, including paintings and sculptures. His recent acquisition of a pair of robotic arms by Tung Wing Hong reflects his attraction to works that elicit strong emotional responses. “Collecting is a lifelong journey, and I may explore new themes as I progress through different stages of my life,” he notes, highlighting the dynamic interplay between personal growth and artistic exploration.

For those keen to initiate their collecting journey, Chu offers practical advice, emphasising that missteps are an inevitable part of the process. “Everyone makes mistakes, but there is no such thing as a wrong collection,” he reassures. “Living with your art allows you to discover deeper connections with both the artwork and the artist.”

In the current art landscape, characterised by rapid evolution—particularly through the emergence of artificial intelligence and digital media—Chu cautions collectors to prioritise authenticity. He poses a critical question: “If it can be produced effortlessly, does it lose its significance?” In contrast, he advocates for a balanced engagement, urging collectors to immerse themselves in the physical world and authentic artistic expressions. “Perhaps we should reduce our screen time and spend more time in the real world—meeting people and experiencing authentic art.”

Chu’s emphasis on emotional resonance, personal connection, and the significance of research provides valuable guidance for those embarking on a collecting journey, reinforcing the idea that the essence of collecting transcends aesthetics—it lies in the experiences and relationships we cultivate along the way.

Monica Hsiao and Henry Chu’s distinct collecting journeys converge on a shared belief in art’s power to enrich lives, foster connections, and reflect the human experience. Each artwork they acquire tells a story, inviting dialogue and encouraging new collectors to trust their instincts. Their patronage not only supports artists but also contributes to the cultural vitality of Hong Kong and beyond.

Fogo Island, off the northeast coast of Newfoundland, Canada, is often described as the end of the earth. “It’s a very remote but naturally abundant place. The lack of distraction allows people to rest and have moments of productivity,” says Billy Tang, executive director and curator of nonprofit space Para Site, who explains it is the perfect spot for an artist residency.

This past summer, Para Site partnered with Fogo Island Arts and the Museum of Contemporary Art Toronto to launch the Fog & Mist Residency, a pilot project offering emerging Hong Kong artists the chance to stay on the island for three months. The first participant was Wong Winsome Dumalagan, a local artist known for her experimental videography and installation work.

Wong is among a growing number of Hong Kong artists pursuing residencies across the globe. Aside from an opportunity for cultural exchange, immersion in a different environment inspires experimentation, improves visibility, and can sometimes even transform an artist’s practice.

“In the art industry, there is constant pressure to perform and a rush to produce new work,” says Tang, who sees a residency as almost an antidote. “Residencies allow more time and space to expand the horizons of one’s practice. Young artists can also be emboldened to take risks.”

Wong was initially sceptical of residencies as her work typically emerges from more spontaneous travel, such as a recent trip to the Philippines, where her mother is from. “But this was unexpectedly suitable,” she says of the long duration of the residency. She was fascinated to discover several Filipinos working in the fishing industry on the island. “It was important to build friendships [with them] during this period. It takes time for me to feel confident enough to talk about other people’s stories to be certain I am not exploiting them,” she says, explaining that she recorded conversations with people in the community and is now reflecting on how to shape this into a work.

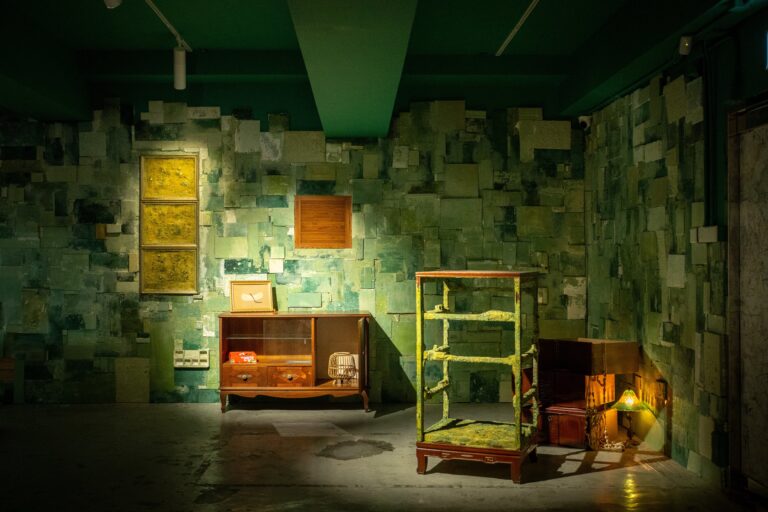

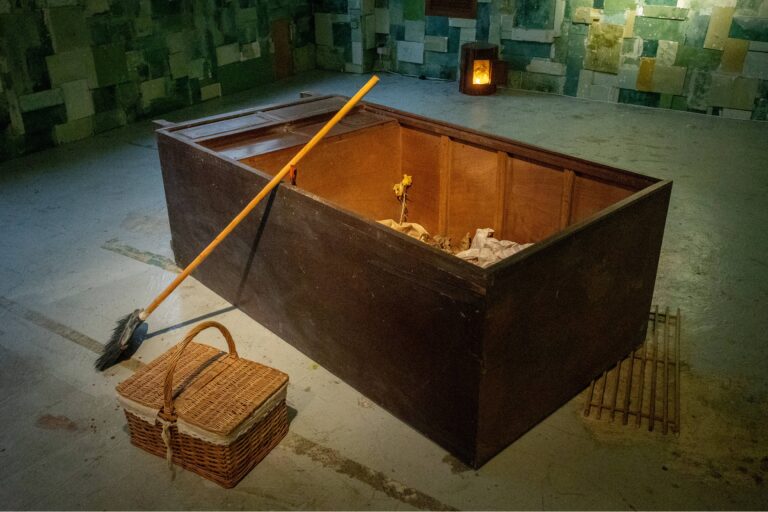

While Wong travelled to a remote island, other artists are finding new possibilities on their doorstep. Local artist Chan Ting, for instance, recently completed a residency at Para Site, transforming its tenth-floor annex space into a cabinet of curiosities. They scavenged the Quarry Bay neighbourhood for abandoned furniture and discarded materials, which they used to create a moody installation. Chan also enveloped the walls with found materials creating a mosaic, which they painted green. The colour referenced moss, an organism that grows in uninhabitable spaces and symbolises the community’s resilience. Chan also played recorded sounds and conversations from the neighbourhood, which added further patina to the immersive exhibition.

Working on this large–scale show was a confidence boost for the recent graduate. “A residency doesn’t always have to be results–orientated. It can also be about giving space that they wouldn’t normally access. For Chan Ting, the residency came at a crucial moment in their career as they were considering the sustainability of being an artist. This was a form of encouragement,” says Tang, who adds that Chan also received an offer from a gallery to represent them in the process.

For some artists, residencies inspire a more concrete shift in style and materials. Local artist Fatina Kong—known for her dreamy images of Hong Kong cityscapes—for instance, had a transformative experience in Xining during an apprenticeship in 2018, learning Buddhist Thangka painting. Often waking up at 6 a.m., she painted until late evening daily for about 40 days. While she previously relied on Western perspective drawing, the ideology of Thangka paintings inspired her to explore more creative compositions. She also started to integrate mineral pigments into her work.

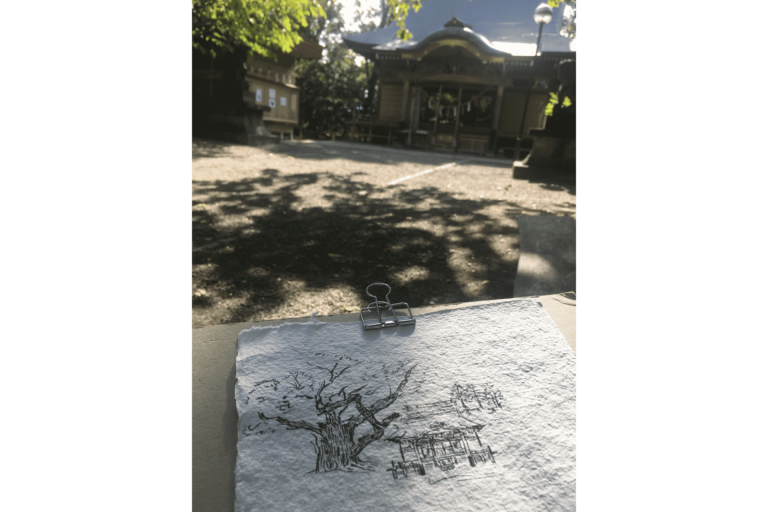

Later that year, she travelled to Japan, where she participated in her first residency at Tenjinyama Art Studio in Sapporo. There, she became fascinated with the rituals of the Indigenous Ainu people and their beliefs about the natural world. Learning about their culture spurred her to explore mythology and poetry as new sources of inspiration. She also began plein-air sketching in Japan. “The different climate and completely unfamiliar scenery had a major impact on my practice,” she says.

Movana Chen, who is known for creating intricately woven paper installations, shared a similar experience in New Zealand at the Nock Art Foundation. While she studied painting during her bachelor’s degree, she soon veered away from the medium when she began knitting with paper. “The dramatic landscapes of New Zealand inspired me to paint again, but this time, it was based on my feelings instead of just focusing on technique,” she says. “Now it’s part of my daily practice to sketch and draw landscapes.”

Chen has done multiple residencies and sees travel as critical to her practice. In 2016, she took a 68-hour train ride to the Siberian city Krasnoyarsk to participate in a book fair and do an artist talk. Chen saw the journey as a type of artist residency. She recalls sharing a cabin with Russian soldiers. Despite language barriers, she communicated with them through drawing. “I was sitting on the lower bunk knitting [strips of paper], and they were curious. I didn’t introduce myself, but the magic of paper and the artwork connects people,” she says, explaining that they tried knitting and even participated in an impromptu performance involving wearing one of her paper “body container” costumes: “My artwork is about people. If you have an open heart, experiences come when you aren’t expecting anything.”

Chen has recently completed a self-curated residency in which she travelled from Portugal to Switzerland in her camper van with a filmmaker and performer for 23 days: “You don’t need to wait for an organization to invite you to do a project. You can curate a residency yourself. The world is calling you. So let it happen.”

Gen Z is stressed. For young artists in Hong Kong, who have lived through a challenging period in their late teens, life hasn’t been easy. Yet difficult times often brew groundbreaking ideas and sharpen people’s awareness of their surroundings, evidenced by the graduation exhibitions in Hong Kong this year. Despite spending half of their university life on Zoom, the art graduates of 2024—from the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK), Hong Kong Baptist University (HKBU), and Hong Kong Art School (HKAS)—exhibited a shared concern on individual relationships with others, their attentiveness to the pressing issues in the society, and their capability to embrace life’s unpredictable nature.

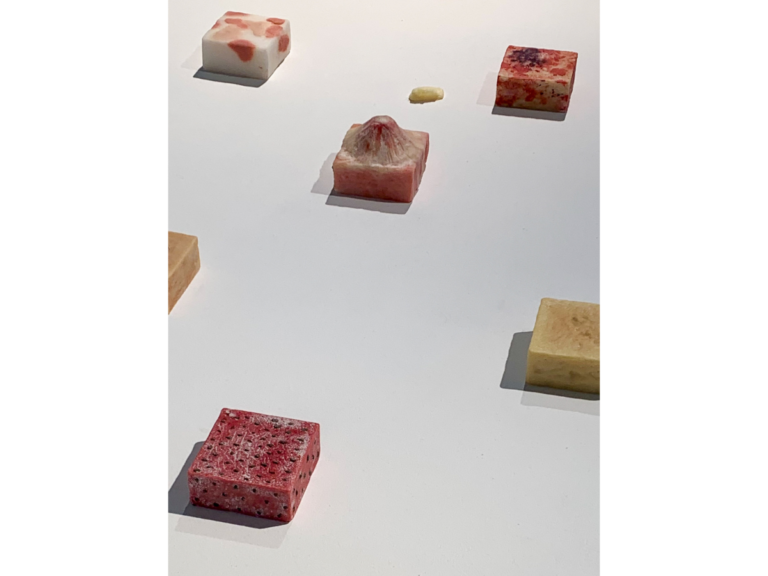

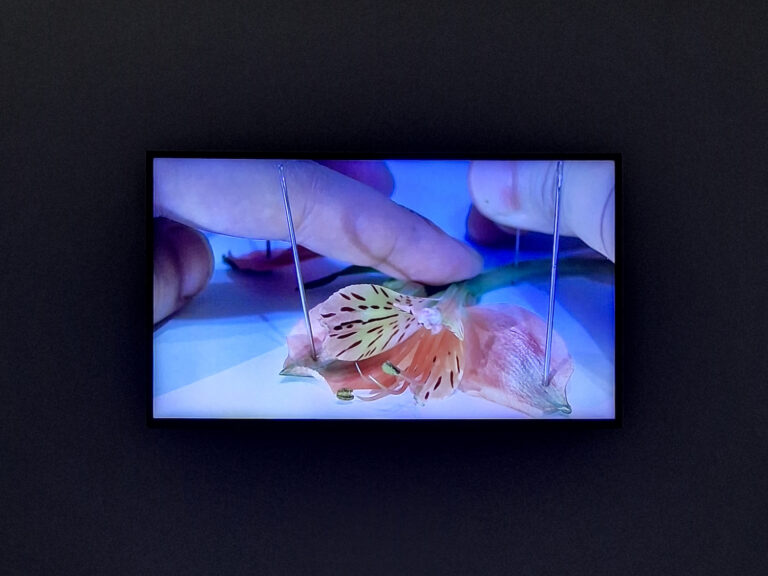

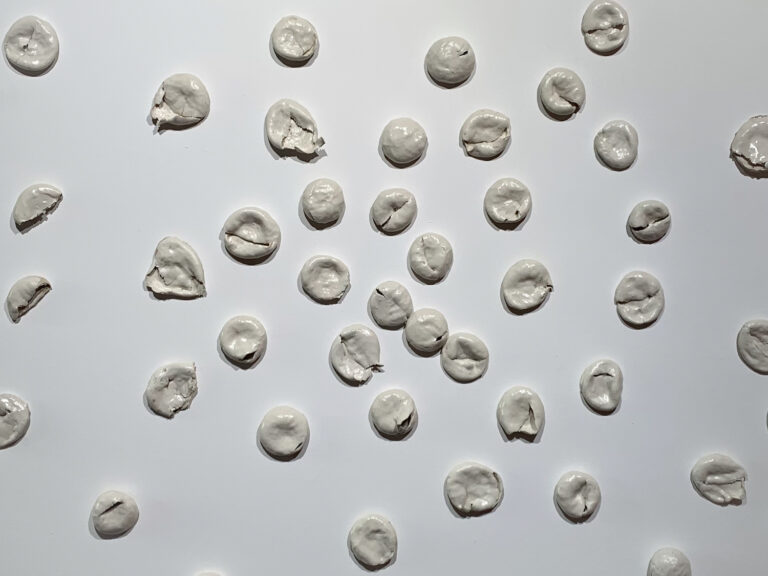

The graduation season was kicked off by “Opus,” held at HKBU Academy of Visual Arts’s Kai Tak Campus, the former Royal Air Force Officers’ Mess. Daring in the use of mediums, these artists revealed how emotional landscape and common misbeliefs are often reflected by objects in the domestic environment. Some works made me feel nervous. Wong Cho Tik’s installation Tides of Tenacity / Waves of Neuroplasticity (all works 2024, unless otherwise stated), for example, comprises more than 200 used orange prescription bottles, occupying the corner of a room like a beehive. In resemblance to genetic structure, the work represented the endurance in pain and the collaborative effort in recovery. The bars of soap in Erica Cheung’s Soap me reminded me of acne, freckles, and eczema, evoking one’s anxiety about their looks. While soap is generally seen as hygienic, here they look unpleasant and disgusting, questioning one’s pursuit of perfection for appearance. In a more disturbing gesture, Janice Wong’s five-minute-long video /seɪv/ details the process of dissecting a flower and discusses the condition of emotional manipulation while stirring a sense of discomfort within the audience. While one might habitually suppress their negative emotions, for Zeng Xiaoru’s Shaped, the artist invited participants to throw clay onto the wall as stress relief. The results speak of the quiet violence brought by suppressed emotions.

![Lo Wing Shan, Did You Ask Today? [nei5 gam1 jat6 man6 zo2 mei6], 2024, seal stones, cinnabar paste on paper, laser engrave on wood, dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist and The Art of CUHK.](https://artcentralhongkong.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Lo-Wg-Shan-768x576.jpg)

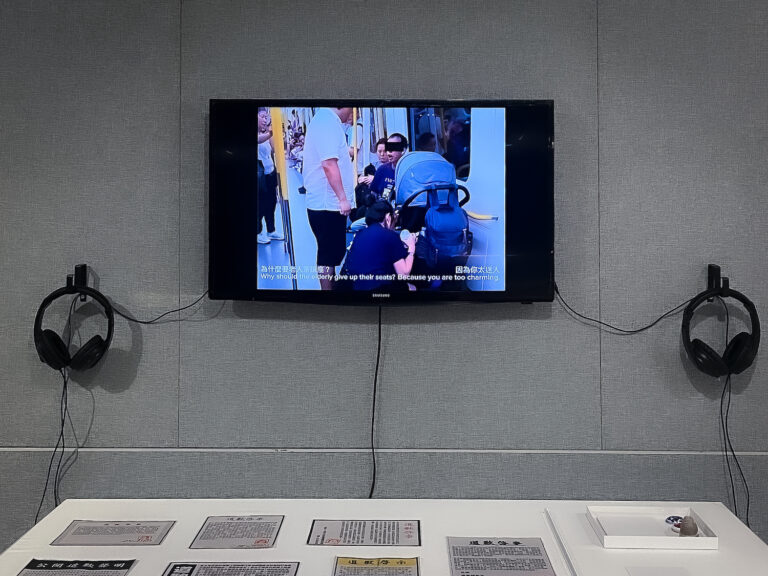

The next day, “The Art of CUHK” launched the projects by both BA and MFA students across CUHK’s campus on a hillside in New Territories. The scale of the two-month-long event was comparable to a mini art festival. I almost got a heatstroke waiting for the bus and trekking uphill while figuring out the routes, but it was all worth the effort. As a university that honors Chinese literati traditions, CUHK’s Department of Fine Arts is known for its emphasis on the spirit of craftsmanship, which, I’ve felt, was embodied by the works at the BA exhibition, “Once in a Blue Moon.” The delicately carved seal stones in Lo Wing Shan’s Did You Ask Today? [nei5 gam1 jat6 man6 zo2 mei6], for example, recall the ritual of drawing fortune sticks at the temple. I was tempted to draw the seal stones from the box and match the images with the Chinese interpretations on the wall, but I chuckled at the texts “YOLO” and “I know nothing.” By including these arbitrary responses, the work provoked thoughts on people’s over-reliance on divination tools in search for harmony during turbulent times. Also incorporating chop stamps was Jennifer Lee’s installation Trilogy of Love, which includes a pile of “apology letters” and a series of viral videos capturing quarrels on Hong Kong’s public transport but playfully dubbed with compliments and expressions of love. While highlighting the precariousness of human relationships, the work also teased the possibility of mutual understanding and love, which are often lost in miscommunication. The sense of warmth continued in a nearby work mounted on the wall, Chan Nok’s Longed For, which features photos of neighborhood windows lit by a small light bulb inside each of the wooden boxes. Taken by Chan during his night walk, these windows represent the boundary between individuals as well as the ambiguity that allows for possible interactions. No longer self-absorbed in their world, these artists bridged traditions with shared sentiment felt in the contemporary society and asked the audience to reconsider the possibility of human relationships.

One month later, HKAS’s exhibition, “Ephemeral,” opened at Hong Kong Arts Centre (HKAC) with a focus on the concept of memory, temporality, and transience of life. A 26-year-old collaboration between HKAC and Melbourne’s RMIT University, HKAS encourages students to establish their artistic identities through innovation and rigorous critique. In Connie Lau’s installation and watercolor paintings, Remembering and Forgetting (2023–24), even expiry date labels are expiring with their ink fading away, which echo the inability of all to withstand the test of time. Limited time was also felt in Carmen Lam’s installation Still – Life (2023), featuring a black-and-white photo projected onto the wall, an empty photo frame, and her father’s chair. While the audience’s time passed, Lam’s impression of a living space in the past was recreated and erased repeatedly in the work, as if they slid in and out of her memory. Carol Leung adopted time’s ability to heal in her work Bloodline (2023), which shows her father’s image gradually disappearing on thermal papers, next to her mother’s photo warmly reprinted in a frame, as an effort to reconcile the pain brought by her original family. These philosophical takes reflected the artists’ ability to heal interpersonal relationships and adapt amid drastic change in life.

When our relationships with others in real life are at stake, we go online to look for consolation. Janet Cheung’s fourteen-part Cantonese porcelain, Stations of LIHKG (2022–23), took inspiration from Via Dolorosa (Jesus’s route to his crucifixion) and illustrated local stories of suffering shared by people on the notorious online forum LIHKG—the Hong Kong equivalent of Reddit. Infused with humor, the work showed how online space is often utilized as a channel for emotional release and even self-redemption. Just as Cheung was inspired during the time of isolation at home, the past few years, though difficult, granted the artists a chance to delve into the events around them. By negotiating the limitations in life, the young artists in Hong Kong have carved a path to navigate through the chaos.